|

Britannia Moribundia |

|

Home

|

This is where England most truly excels: in all the characterful shabbiness of its drizzled parks, soiled launderettes, frayed tailors, abject chemists, sparse barbers, bare foyers, dun pubs, weary Legion halls... and cowed solitary cafes. From an era when Britain Could Have Made It, these silently wasting emblems of Britannia Moribundia - that chronic malaise of managed-decline and shattered public services that clings to the country like a pall - are now confined to reproaching the double mochha latte merchants subsuming them. Here then, as the cultural shadows lengthen, are some inspirational pieces from authors with their fingers - knowingly or not - on the faltering pulse of a worn-out, dingy and cherishably threadbare UK in its terminal phase. (Click here also for the recently discovered Hotel Moribundia in full pride and plume).

Anita Brookner, Diva

of Desolation: Independent [18 Feb 2005] David Cracknell: The

Sunday Times [2 Jan 2005] Oliver Bennett: The

Sunday Times [24 Oct 2004] Mark Fisher/K-Punk:

k-punk.abstractdynamics.org [19

Feb 2004] Undercurrent [Feb 2004] Patrick Sawer: London's

Melancholy Underbelly Evening Standard [4 Feb 2004] Simon Reynolds: Blissblog [19 Feb 2004] Michael Bracewell: The Independent [22 Feb 2004] NEW To a particular kind of cultural tourist, the seaside towns of England have always articulated an extreme form of romanticism, firstly in a literary idiom which would then be updated by pop. From TS Eliot's apostatical reference to Margate Sands, through Paul Nash's essay on "Seaside Surrealism", to the "sopping esplanade" from which WH Auden predicted England's decline, the seers of British modernism set out a particular - and enduring - relationship with the ritual landscape of the English coastal holiday. I suspect that what they found there, in the protracted twilight of Edwardian gentility, was the quality Frank Kermode described as "the sense of an ending". That in some heightened poetic way, the bandstands, ornamental gardens and chilly vistas of our old resorts held a mirror to the passing of an epoch - to the gradual dimming of an earlier gaiety. In this, the English seaside towns have developed an allegorical identity - a mood of acute romanticism in which they recollect their past within their present. In their every detail you can glimpse an earlier age - the more so in those run-down resorts which seem to articulate Graham Greene's pronouncement that, "Seediness has a very deep appeal; it seems to satisfy, temporarily, the sense of nostalgia for something lost; it seems to represent a stage further back." Such a relationship to nostalgia has a perverse kinship with glamour - perfect to re-enchant the whole world of pop. And as the seaside towns developed in step with the history of popular culture, so in their dance halls, wintergardens and ballrooms you can feel pop's ghosts around you... Towards the end of the 19th century, the bravura sweep of Morecambe Bay had earned it the label, "The Naples of the North", and the resort's popularity had been confirmed in the early 1930s by the construction of Oliver Hill's breathtaking art deco Midland Hotel. By the early 1950s, the bathing beauty pageants at the Super Swimming Stadium were attended by thousands of visitors, while over at Heysham and neighbouring Middleton Sands, two big holiday camps - one built to resemble an ocean liner on dry land - combined the vivacious pleasure-seeking of the first pop age with the coast's reputation for having some of the most dramatic sunsets in the world... the conceit of the sunset seemed to be its defining image. Morecambe had even been advertised, in the 1930s, as "The Sunset Coast", while in a more impressionistic sense the colours of the lingering twilight seemed to comprise an elegy for the long departed seaside carnival... those fading grand hotels, silent boarding houses, dormant ornamental gardens and windswept piers is both an ultimate expression of Englishness and its plangent requiem - the "sense of something lost", perhaps, prompting nostalgia for a former innocence. It's a moment which John Betjeman caught in his poem a bout wartime Britain, Margate 1940, and which, at the beginning of the 21st century, seems equally relevant to the sci-fi lullaby of today's coastal drift: "And I think as the fairy-lit sites I recall/ It is those we are fighting for, foremost of all." Tony Parsons: Daily

Mirror [Nov 10 2003] NEW Nick Cohen: Observer

[Oct 12 2003] NEW Stephen McClarence:

The Times [22 Jan 2000] NEW Nikolaus Pevsner visiting Scarborough in the 1960s for his Buildings of England commented on the town's : "High Victorian gesture of assertion and confidence, of denial of frivolity and insistence on substance than which none more telling can be found in the land" Scarborough started out as a spa, full of classy shops. The classiest of them has only recently closed: Greensmith and Thackwray, Indian and Colonial Outfitters, was the place to stock up on pith helmets and plus-fours. Now only its trim gold sign survives, an odd fragment of imperial splendour on the no-nonsense Yorkshire coast. There is still plenty of Victoriana to while away a cold winter's day. Among groves of laburnums, Wood End, a natural history museum, is the former home of the three Sitwell siblings whose library - through a conservatory of potted palms - is lined by forgotten books that raised a small literary storm a lifetime ago. Customers at the town's Harbour Bar are brace themselves for the day's first chocolate nut sundae or vanilla milk shake float and a waitress is spooning red jelly into a glass bowl. The bar, little changed since it opened in 1945, is one of Scarborough's greatest glories. Its decor is a sunburst of yellow and white, a banana split recreated in Formica. The walls are lined by mirrors and slogans. "Get your vitamins the easy way," "Eat ice cream every day." Or: "Ice Cream! Nutritious! Delicious!" Nick Cave: Guardian/Weekend

[Feb 1 2003] NEW Nick Foulkes: Evening

Standard [Nov 2001] The lino floors; the electric bar heaters; the sewing machine that was second-hand when the owner's grandparents bought it in the early 1900s; the jazzy pine-effect wallpaper that creates a bizarre faux-Scandinavian wainscoting. If English Heritage had any sense it would slap a preservation on the place immediately. Then there is the window display. The recessed double-fronted layout with its glassed-in units creates a mini-arcade and, while it is not quite the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in Milan, it is a showcase for the window-dressing talents of Rita Hemington, who has worked at Blustons since 1946. The homogenisation of our high streets is a crime against our culture. The smart ones get the international clones - Ralph Lauren, DKNY, Starbucks and Gap; while those lower down the socio-economic hierarchy end up with Nando's, McDonald's, Blockbuster and Ladbrokes. Which is why Blustons is wonderfully subversive. This outfitters for ladies of a certain age, and sometimes certain size, is a living museum. Not so long ago, every high street had a Blustons... Instead of forcing itself to fit new trends, Blustons has chosen to age with its customers. "I will stay here and when I feel I have had enough I will either let or sell the shop," says Mr Albert. "A double shop on the high street will always be in demand. Anton Szandor LaVey:

Washington Post Magazine [Feb 23 1986] Iain SInclair: Fortean

Times [Jun 2001] However, I've been less comfortable of late here than ever before. Things are boiling up quite fiercely from this random patchwork of gentrification. As one part gets nicer, so the surrounding bits will become more ferocious. Now those contradictions are starting to bite in a serious way. The latest fright sheet that came through from the council says that car crime involves cars being loaded onto lorries and taken away. There were people being arrested on our square doing crack deals, there've been stabbings -if you'd read all this a few years back you'd think they were describing New York. Superficially it's quite calm, but there have been maybe ten or twelve killings here just lately, and they hardly register. There's ordinary, everyday things too, like the post hardly operates any more, it's completely random whether you get it or not - everything is quietly breaking down. Movement around the city through public transport is impossible. That's one of the reasons I began walking everywhere, because it was quicker! AA Gill: Sunday Times

[Sept 9 2001] Ken Clarke is one of the old devils. The world he would have us slouch in is Kingsley Amis's 1950s. Habitué of smoky jazz bars, lovingly wiping old vinyl with corduroy sleeves before gingerly dropping the Bakelite arm of the trusty old Grundig. Lover of soggy bacon sandwiches and brown

sauce, of company dinner dances and surreptitious continental

weekends, of minor public schools, minor ambitions and minor

vices, his scuffed Hush Puppies jabbing the unresponsive pedals

of a reluctant MG to motor into the country for a pub With Two-Way Family Favourites on the wireless and a tartan travelling rug in the boot, Clarke's England is a place of seedy, comfortable decline, of clubbable anger and unfinished crossword puzzles, of splenetic punning letters to the editor about the decline in grammar and opening batsmen. A country scratching a lazy irritation at sagging doorjambs and late trains, whose greatest attribute is a collective, smelly tolerance, where a chap will put up with almost everything, which means he won't care about anything enough to get out of a chair. A country of public insouciance and private, grubby guilt, where you can believe anything as long as you don't believe it too fervently. A country where the highest aspiration is for a quiet life and where, as Kingsley put it, the three most depressing words in the language are 'red or white?' Julie Burchill: The

Guardian [Nov 25 2000] The Grand Hotel looms over Eastbourne as defiantly and definitively as the Statue of Liberty loomed over Charlton Heston at the end of Planet of the Apes; it reared up at us out of the night, ice-white and towering, like something out of St Petersburg. All by itself, set back from the road, scorning the neighbouring hotels whose names also recall the glory days of the English seaside - the Albany, the Burlington, the Chatsworth, the Cavendish - you could see why it was known as "The White Palace" in the years between the wars, when the BBC Palm Court Orchestra broadcast live from the Great Hall every Sunday night from 1924 to 1939. Dennis Potter, whose Cream In My Coffee was filmed there, called it "a huge, creamy palace". Opulent yet easeful, the utterly lush reception has greeted everyone from Winston Churchill, Haile Sellasie and Aneurin Bevan to Charlie Chaplin, Arthur Conan Doyle, Elgar, Anna Pavlova and Paul Robeson, These days it may be somewhat reduced to Harold Pinter, Celine Dion and Liam Gallagher, but you still get the essence of the place where Debussy completed La Mer. As far back as the 1880s, the Eastbourne Grand was, a byword for luxury and progress going hand-in-hand; advertisements boasted of the private omnibus to collect rail travellers, a library and public rooms lit with electric light, a hydraulic lift and separate tables in the dining room. Eastbourne's pier is typically solid, boasting both a newsagent's and a flower shop which we certainly don't have on Brighton pier. Not suprisingly, the tattoo shop had closed down, but the charming Bar Copa at the end of the pier proclaimed itself to be the ideal spot "for sporting and cavorting". There were boat trips on offer, too: cruises round Beachy Head and speedboat rides on the thrillingly named 007. Once again, this was in pleasing contrast to Brighton - where it is easier to get raw opium than a boat-ride. The esplanade was pleasantly melancholic: a sign threatened a whopping £500 fine for cycling on the seafront and a yellowing poster promised The Manfreds with Chris Farlowe, Alan Price and Cliff Bennett (but sadly, no Rebel Rousers) at the Congress Theatre. Best of all, in a basement beneath the Cumberland Hotel, we were Invited to "In-Step Sunday Club: Ballroom and Sequence Dancing with Peter Harvey's Hi-Fi Show". It made me miss my mum and wish Alan Bennett was with me and I thought how very pleasant the old English way of taking one's pleasure was, without all that neurotic chasing about and taking pictures of everything, just so the folks back home will believe you were there. It was about 5pm on a Sunday afternoon, just getting dark, and then the most gorgeous thing happened. We went up the front steps of the Grand and into the lobby - and there, in the Great Hall right in front of us, was a string quartet playing chamber music. Smart old couples took tea at tiny tables, and as we went up in the lift, suddenly it could have been any year between 1924 and 1939. The immaculate Grand could have been the rundown Overlook from The Shining, full of between-the-war ghosts. Being in Eastbourne was in many ways stranger, more foreign than being abroad - particularly the Caribbean, which in its more profitable enclaves can feel like lodging in a luxury franchise of America. But you can occasionally find good parts of Britain - Porthmadoc in Wales is another - where the American takeover seems never to have happened. And never underestimate the refreshing qualities of sneaking off the Yankee yoke, if only for a weekend. Joanne Briscoe: The Independent 'Pleasures of Modern Life' [1997?] Mark Irving: Space/The

Guardian [Mar 2 2000] England All Over Joseph Gallivan [Sceptre] Though he sleeps dreamlessly and is mired in inertia, Clive needs to get a job: Tina is chasing him for maintenance for Tess. He winds up as a guide for Britannia Tours. As the novel's title suggests, this is a dream position: Clive is a dedicated observer of people and place and wants more than anything to travel around the country. What, he wants to know, does it mean to be English? A month or so into the job, he has a very bad day. On a trip to Bath, the coach driver has a heart attack and dies. Later, Clive returns home to find that he's been burgled, although, as he notes to his Kiwi neighbour, he didn't have anything worth stealing; anyway, his ex-wife has taken it all. He resolves to commit suicide. He jumps from a bridge. As he drifts down the Thames, we don't (as up to now) observe Clive, but shift to his perspective. He realises he doesn't want to die almost as soon as he jumps, but after being dragged underneath the churning water, he discovers that he is one of the "lucky 50 per cent of floaters". Gallivan captures this terrifying miniature epic beautifully: the loneliness, the fear, the incidental beauty. Next, Clive wanders the streets, and ends up sleeping rough; everything has a piercing, unnatural sharpness. On Clive's return to work, Gallivan extends this sense of personal panorama to his journeys around the country itself; ironically, while to his clients he is a guide, to us he is a tourist in his own land. Milton, Shakespeare and Wordsworth are all name-checked movingly and unlaboriously. Somehow, amid the standing stones and motorway service stations, castles and crude heritage sites, Clive finds peace. He finally elucidates what the country means to him in a wide-ranging, wild rant at the novel's end: 'Car-boot sales. Vacuum-tube valves. Paddle boats. Roman numerals. Monogrammed hankies. Cones. Knot gardens. Troublemakers. Quink. Asian Babes. Victorian swimming baths. Tartan shopping trolleys. Scabs. Tank crossings. Frog crossings. Pelican crossings. Pigeon fanciers...' And the list, rather brilliantly, goes on." [TIM TEEMAN: Times March 18 2000] Ian Penman: The Face

#96 [Apr 1988]

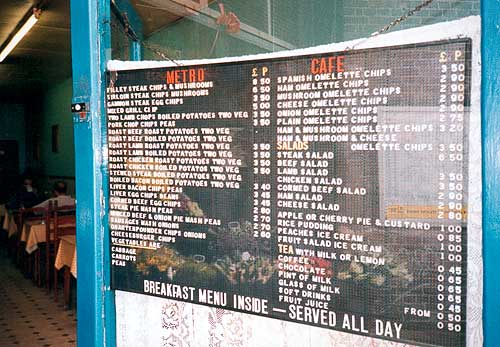

Classic Cafes

| Iain Sinclair interview Classic Cafes | Pellicci interview [ES magazine] Classic Cafes | Lorenzo Marioni interview

|